Michael Neiß, Department of Archaeology & Ancient History, Uppsala University

Data science has brought an exciting new range of methods to humanities research, using computational techniques, such as GIS, 3D-documentation and databases that contain data sets of increasing quantity and complexity. Yet, as digital archaeology is expanding, it is also fragmenting into ever more specialised areas of knowledge. New technologies seem to be superseded with better ones at an accelerating speed. As a result, it becomes increasingly difficult for archaeologists to monitor current technological trends, as well as to integrate the ever increasing amount of ‘big data’ into the theoretical framework of our discipline. Therefore, it seems more than natural to collaborate with digital experts from other disciplines.

My passion for Viking art and crafts has led me into an artefact-oriented line of research, including 3D laser scanning, database development and experimental archaeology. Preliminary results are published continuously, and I participate in various research projects, as well as public outreaches that relate to digital archaeology.

3D Laser Scanning as a Tool for Viking Age Studies

Project partners: Sebastian Wärmländer & Sabrina B. Sholts

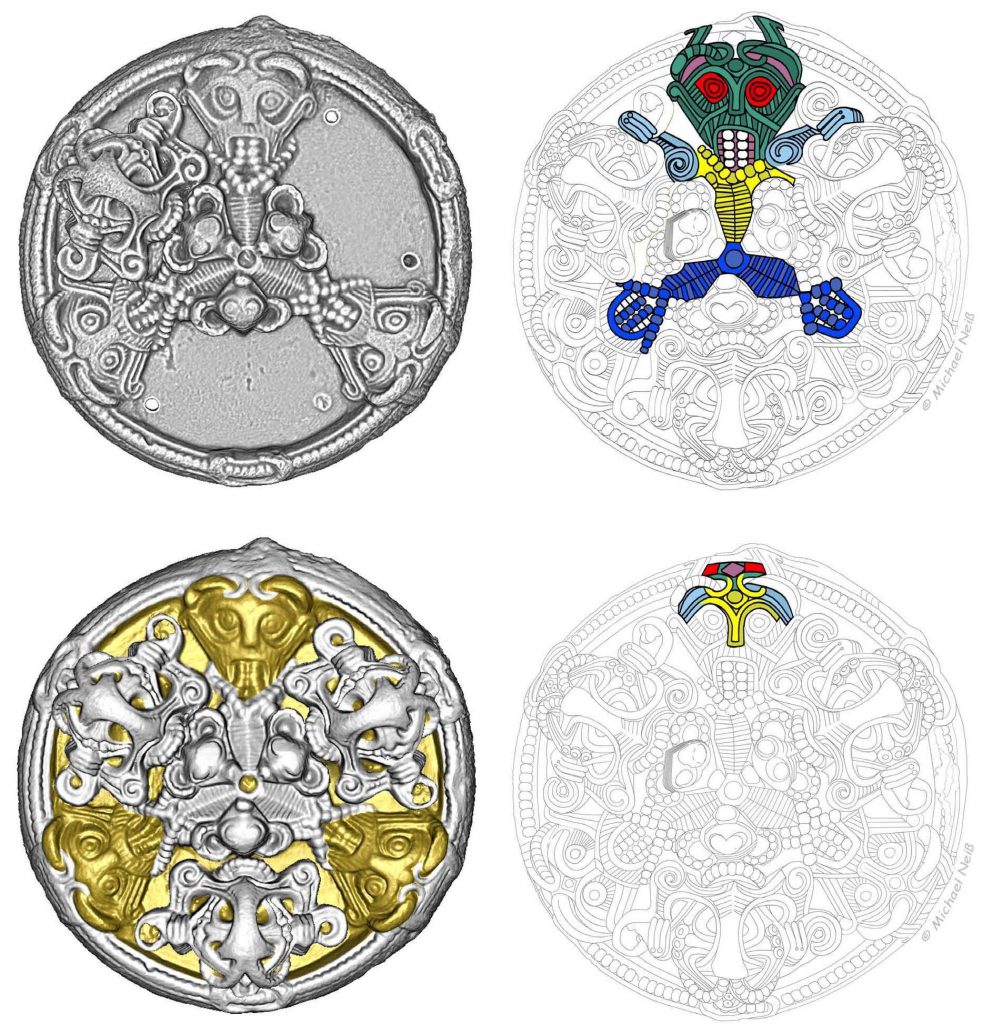

Until recently, 3D scanning was a tedious and rather expensive business. But as the digital revolution progresses, the equipment is becoming cheaper and more manageable. It seemed therefore logical to test 3D laser scanning as an everyday tool in archaeology. Within our pilot study, a broad variety of objects has been digitalized with portable laser scanners. As a result, 3D analysis has proven itself an effective tool for Viking Age studies that opens up the road to creative and innovative research.

Multi Material Crafts in the Early Viking Town of Ribe

Project partners: Sarah Croix & Søren Sindbæk

UrbNet is a research centre that aims to grasp of the cross-cultural process of urban evolution through synthetic studies that employ an innovative high-definition perspective. We propose that the organization of crafts may be a key catalyst for Viking Age urbanism. This was argued through a reassessment of finds from an early metal workshop in Ribe. 3D laser scans were used to classify unidentified mould fragments that derived from different contexts, but arguably belonged together. Our findings motivated a total revision of the local stratigraphy. As a result, we realised that the workshop produced a wide range of metal parts during a short period, instead of several decades – as had been proposed by the excavators. These metal products were intended for composite products like wooden chests, belts, or horse harnesses that demanded the combined skills of several craftspeople. This need for collaboration would have been a decisive incentive for the formation of permanent communities that, further on, developed into Scandinavia’s first towns.

Medieval Casting Moulds from Ribe

Project partner: Mette Højmark Søvsø

The Museum of Southwest Jutland’s collection contains fragments of High Medieval casting moulds from Ribe. Five of the moulds were recovered in the vicinity of the Cathedral, suggesting that metal objects were produced and sold nearby. Those artefacts were either used as costume accessories or for religious veneration. The large number of mould fragments reflects Ribe’s international orientation during this era, with a strong network that involved other towns in Northern and Central Europe. We created virtual casts from these moulds, in order to understand the religious use of the lost originals.