A guest interview with Stuart Dunn, by Dr. Zeta Xekalaki, reposted here with the permission of Archaeology and the Arts Magazine

Digital humanities as a trend has been central in modern scholarship, including art history. The extraordinary development of digital methods and applications aiming in representing, mapping and preserving data seems to change heritage and culture worldwide. Digital humanities offer new insights to sets of information that would remain out of reach with conventional research methods, in order to create new areas of exploration by triggering questions and, finally, to provide the dynamics for a more “democratic” spread of knowledge as the main route to making data both accessible and relevant to large population groups worldwide.

Human-related dynamics is probably one of Digital humanities’ most intriguing features if we think of the massive changes we are witnessing. One way or another, we all experience global change that results in massive human ‒ and cultural ‒ migrations that rapidly change our cultural surroundings. Such events also affect the heritage map, with iconic monuments vanishing, falling victim to extremism, military activity or neglect. Through the above, mobility becomes a central concept in perceiving the world for culture and heritage experts, including the ones having to do with studying the past. In that sense, archaeology and art history both proceed from seeing objects within a set time and space to watching them as they “transgress” across time and space, from one to another. More than ever, cultural heritage research now focuses on mapping “itineraries” of art objects.

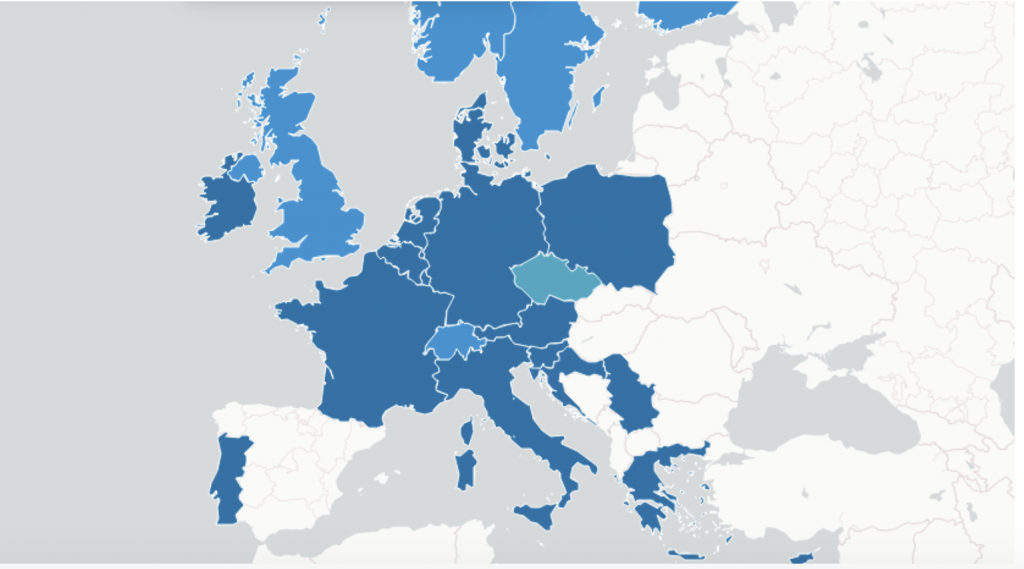

Dr. Stuart Dunn (King’s College London) is one of the academics aiming to develop and improve ways of mapping those itineraries in art. With an interdisciplinary background encompassing the archaeology of Bronze Age Mediterranean, paleovolcanology and spatial archaeology, Stuart is now the principal investigator of “Ancient Itineraries”, a project of the King’s College London’s Department of Digital Humanities, funded by the Getty Foundation as part of its Digital Art History Initiative. And this was the project that recently brought him to Athens, guiding a group of international researchers from various backgrounds in the project’s second meeting, following a first one in London. Following a fruitful conversation for all-things-“itineraries”, Stuart kindly accepted to answer a few questions, sharing his view about archaeology, art history and digital humanities with the readers of Archaeology & Arts.

Zeta Xekalaki: Thank you for speaking with us! I would like to start with a question about your own “academic itinerary”. Throughout your academic life, you combined archaeology with natural sciences and now with tech. How did one bring the other?

Stuart Dunn: My own origins were very “non-digital”. I was a library-based archaeologist and surveyor, who was particularly interested in problems of how we date particular types and periods of human activity in the Helladic and Minoan Bronze Ages, and how these relate to one another in both space and time. As I was dealing with more and more data which had been created, described and published in many different forms, it became clear that I needed more than just pen and paper to create meaningful maps and models of all the different kinds of evidence. Looking for solutions, I first discovered Geographic Information Systems, and my life changed! Since then, I have become more and more interested in how we can use GIS, and related technologies, to explore the human past, with all its complex, fuzzy and, in some cases, undefinable datasets.

Z.X.: Digital humanities’ applications in archaeology and art history have met an impressive rise for a while now, and the trend keeps going strong. What do you think brought that rise?

S.D.: I think the main reason for this is that history and, more particularly, archeology, already have a very strong basis in quantitative methods. There are debates going back to the 1970s, possibly even earlier, on how we use such quantitative methods, such as mapping and statistics, in the study of the past. That’s why there is so much GIS in archaeology, for example than in other branches of the humanities. However, similar debates have also been going on for a long time in textual studies and corpus linguistics. For a variety of reasons, I think these have been more readily defined as “Digital Humanities”. So really, I think this is as much a matter of semantics and perception as anything. Interesting and valuable applications of computational methods have always been there across most branches of the humanities, we just call them different things. But it’s clear to me that some of the crossovers we are now seeing between these ways of thinking in the last ten years or so is forcing us to rethink what we mean by that the term “Digital Humanities” itself. And that’s a good thing.

Z.X.: From what you see, which do you think is currently the main challenge for art history on which digital humanities is more likely to respond positively?

S.D.: We have recently seen a series of fascinating debates on the benefits to art history of digitization, and of computational approaches of the kind referred to above. Some art historians have embraced them, others are skeptical. For me, the most important thing is that digital methods will never replace discursive practices such as interpretation, understanding of connoisseurship and stylistics. For me, the need is to understand what digital methods can add to these. For example, we need to improve our understanding of how art and its receptions function in digital society. What does it mean now that “the digital” can play as much of a role in mediating art as a gallery? What are the dangers and opportunities of this for scholarship under the critical understanding of art?

Z.X.: And, what is now the main challenge for digital art history, according to you?

S.D: Much the same!

Z.X.: Do you think that an archaeologist or an art historian now should certainly have some knowledge of digital humanities’ methods?

S.D.: I have always believed that interdisciplinary research works best where the guiding principles are inclusivity and sharing. Therefore, I would not say that one should necessarily have skills X, Y or Z to participate in digital humanities. This goes the other way. For example, are there any specific, concrete skills without which you cannot be called an “archaeologist”? Probably not. After all, who gets to decide if you even have such skills or not? By the same token, I would certainly not argue that someone identifying as an art historian or archaeologist must have digital skills.

Z.X.: Now, let’s go to the project that brought you to Athens. Ancient Itineraries. How did you come up with this name for the project?

S.D.: The main rationale of the project is to examine how digital methods, broadly defined, can support and expand our understanding of ancient art objects – the stories of those objects – and through them, the past more generally. From this perspective, one of the most interesting aspects of such objects is how and why they move from one context to another, and how this helps us to address questions of cultural influence, appropriation, and representation. These questions can also trip up archaeologists and historians. For example, there are lots of Greek art objects in London. If London were destroyed and all context lost, might this lead archaeologists a thousand years from now to believe that London was once ruled by Greece? Understanding how and why objects move is important. It, therefore, seemed important to come up with a name that expressed the complexities of art moving from one context to another. “Itinerary” implies not just movement, but the reasons for it, who might be responsible for it, and perhaps most importantly, things that happen along the way.

Z.X.: Ancient Itineraries’ object certainly points to something being on the move across time and space. Is this “something” people, objects or both?

S.D.: Exactly. Most archaeological approaches start from the physical object as the primary focus of study. When you introduce the traditions of history and art history, you need also to start considering the stories (and itineraries) of people as well. But ideas and styles also travel and diffuse between cultures. We are also interested in these more abstract types of itinerary.

Z.X.: Ancient Itineraries as a project is based on three methodological topics: provenance, geographies, and visualization. Why did you choose these topics?

S.D.: We wanted a methodological focus which reflected previous work on digital art history, with linked foci on objects and the relationships between objects. These three areas seemed to do this most comprehensively.

Z.X.: Something that confuses me a bit: what is the difference between geographies and provenance?

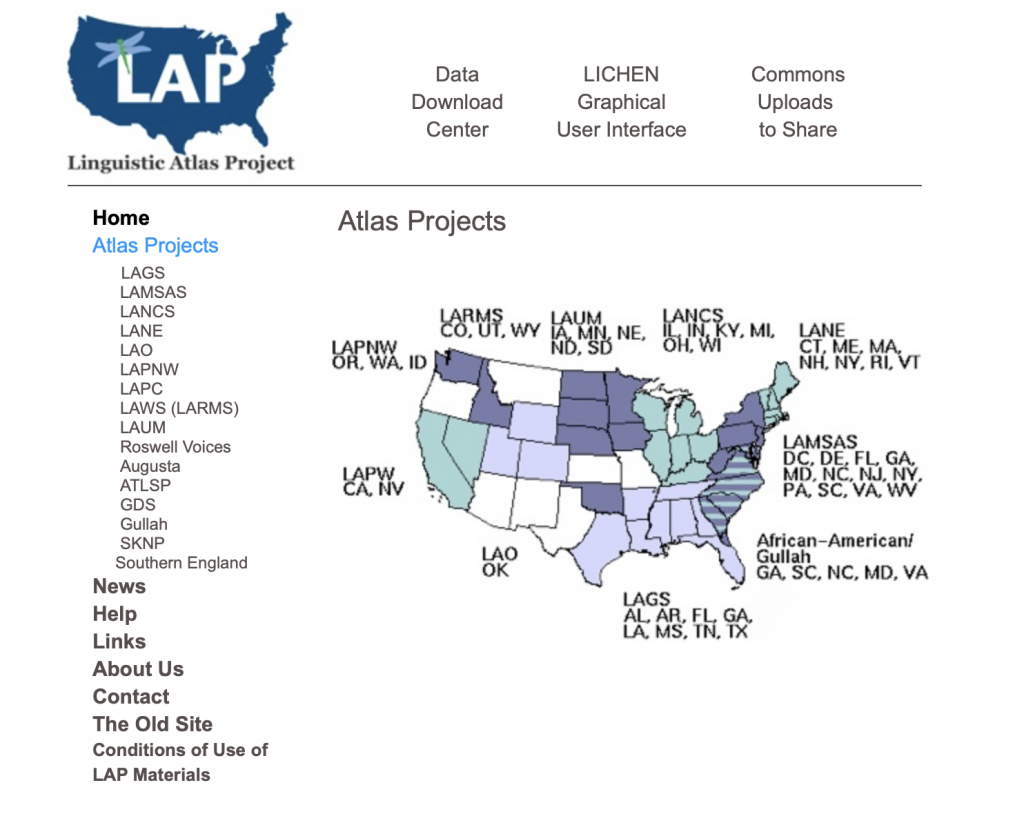

S.D.: Both the project’s meetings considered the definitions of these terms in great detail. In a conventional art history sense, “provenance” would be understood to be the descriptive dataset which describes where an object originated. However, the fact that we are also interested in where it has been since then means we also need to consider its geography, which is its relationship with both physical and conceptual place. This enables us to draw on a wide range of digital methods and tools, such as GIS and Recogito, which are designed to help scholars deal with geographic data.

Z.X.: Why the Classical world was chosen as the cultural context to test and develop your case?

S.D.: Quite simply because there is a long pedigree of excellent work in the area, which has resulted in a rich array of digital methods, projects, and linkable data which relate specifically to Classical antiquity. This includes the Pelagios project and Recogito, the Pleiades Gazetteer, Linked Pasts and so on. Our work during the meeting in Athens with the Recogito project highlights these synergies.

Z.X.: In your blog, you clearly set that Ancient Itineraries aims at producing “a Proof of Concept (PoC) for digital art history research”. Would it be a bit challenging to tackle such a diverse context with a product made through case-studying the Classical world only?

S.D.: I don’t think so, for the reasons stated above. In fact, it would be far more challenging to attempt a Proof of Concept which addresses all regions, periods and definitions of art, so we needed to specify. Confining the Proof of Concept to the Classical world gives us some logical boundaries of scope. However, these boundaries themselves are not unproblematic – who gets to decide what “the Classical World”, or “Classical art” is? But at least it gives us a definition to start from, and at the same time allows us to problematize these boundaries.

Z.X.: Can you describe the Proof of Concept produced?

S.D.: We are still working on defining this. Methodologically, I think I can say that we will try to follow in the footsteps of the digital projects which have gone before, as described above. These have sought to describe and link existing datasets together in smarter ways. We will try to do this in a way which addresses the particular issues of art history.

Z.X.: Following the recent destruction of Notre Dame in Paris, the methodology resulting from Ancient Itineraries seems more relevant than ever. Can you describe the way to utilize this methodology as developed in the project’s proof of context, with Notre Dame’s repair as an example?

S.D.: This is quite a “horizon scanning” question. However, imagine if we could take digital architectural models of Notre Dame, such as those recently highlighted by National Geographic magazine, break them down into individual components, and then link those to online descriptions of the cathedral. These could be journals and travelogues – there is a mass of such material now digitized, especially where they’re concerned with places like Paris which are very culturally valuable – or more recent and less formal sources, such as tourist sites, blog posts, or even tweets and Instagram photos. This could enable us to retrieve not only what the cathedral, and its art, and its architecture looked at (at a given time), but also capture human responses to it. But for this to be useful, we would have to have a close understanding of each digital object, its own provenance, and how it links to other digital objects.