Virginia Boyero is an associate producer at Massive Entertainment – A Ubisoft Studio. Independently from Massive she is a participant of the Kulturarvsinkubator from Riksantikvarieämbetet with her project on historical cartography.

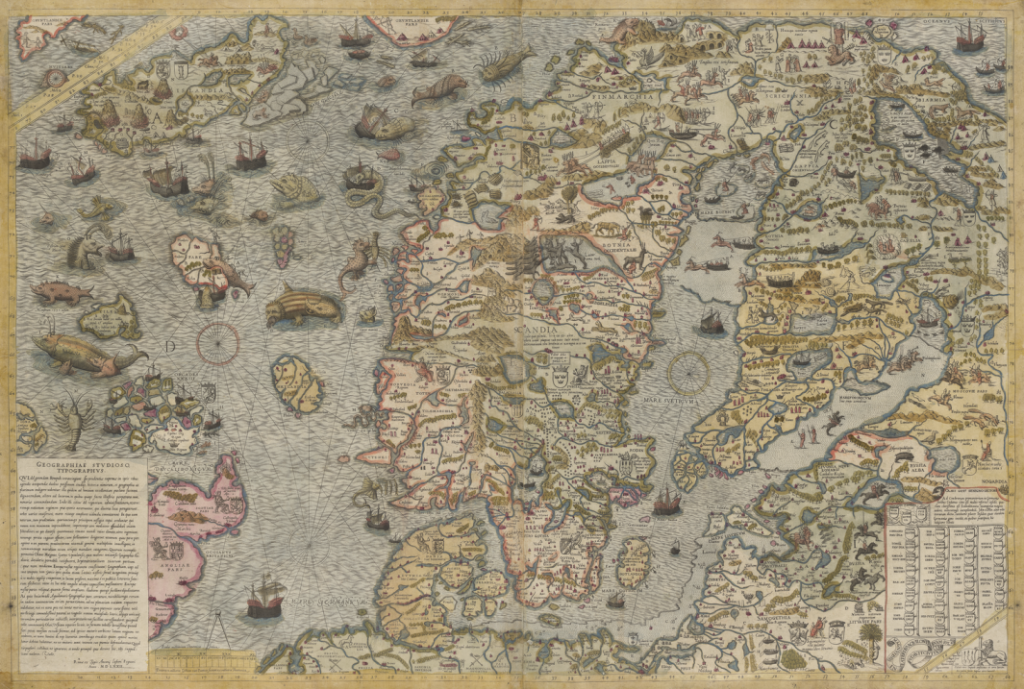

I have always been fascinated by maps. With the abundance of digitized materials from museums, archives and libraries all around the world, exploring the beauty of historical maps has never been easier.

Technology like IIIF allowing deep zoom into high resolution images invite to take one more step into the world of maps. But how can we go even deeper, beyond the surface of the map and really take advantage of the document being digitized? Having worked in the videogame industry for almost 14 years, I have grown accustomed to the ease of access of games, the fluidity of the menus and the immersive experience that allows you to interact with the environment and become a part of the world. Turning back to my original upbringing as a historian, it seems I had taken for granted the powerful tools that we rely on when building games, and historical maps, with all the wonder and possibility that they inspire, literally felt as flat as the .jpgs they were.

What if it was possible to take a virtual tour of Hamburg in 1591, and hear the description of the town from a traveler at the time? Learn about the cost of a meal, the conditions of the sleeping quarters at the inn, the time it takes to travel by coach to nearby Lubeck, or the perils of the road ahead towards Italy? That’s only the beginning of Fynes Moryson journey, which expands across Europe and Turkey for the most part of the decade.

The natural aspiration of viewing digitized materials in a more cohesive way, breaking silos between institutions but also between realms, bringing together literature, archaeology and art in a single platform is becoming a reality. With the contribution of engaged and passionate communities like IIIF and the Pelagios network, it feels exhilaratingly imminent. In Sweden we are also lucky to have state initiatives like KAI, the incubator for digital cultural heritage that promote this kind of thinking and innovative uses.

Though it is still in its early stages, perhaps with the help of annotation tools like Recogito, and the engaged community of volunteers that devote hours of their time to diverse crowdsourced projects in platforms like Zooniverse, tying the maps to the art and literature of their time might see a light of hope. An exciting long journey ahead.

http://libris.kb.se/bib/17257725